|

相關閱讀 |

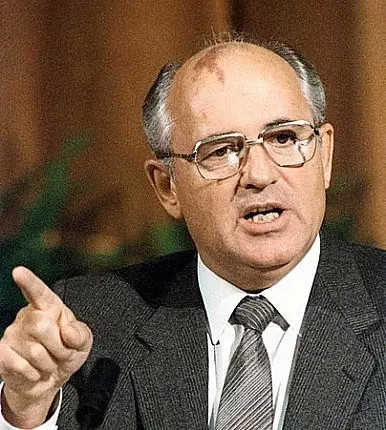

Being a Successful Gorbachev?(做一名成功的戈爾巴喬夫?)

|

>>> 名人論史——近當代作家的史學觀點 >>> | 簡體 傳統 |

歡迎分享轉發 To be a “successful Gorbachev” requires holding all levers of power in order to push through deep reforms. By Yang Hengjun March 18, 2014 The host invited me to talk about today China’s political situation. But to talk about this, I would want to complain and to criticize, and I long ago made a rule: not to criticize China overseas. If I’m going to criticize China, I will return to China first and then proceed. So today, I can only talk about Gorbachev, a foreign retired leader, more than 80 years old. Talking about him is very safe. From the common people to the leaders, China’s “Gorbachev complex” is very serious. There are people who hope that China will soon have its own Gorbachev, and there are also people who are trying their hardest to avoid the emergence of a Chinese Gorbachev. For those who want a Chinese Gorbachev, it’s because he was committed to reform, almost single-handedly ended the Cold War, toppled the powerful but fairly sinister Soviet empire, and brought democracy to Russia and other countries. Others hate Gorbachev because his reforms failed. Not only did he cause the downfall of the ruling Communist Party, he also made a superpower crumble overnight. Plus, the democratic transitions in the ensuring 20 years have not been smooth. Were Gorbachev’s reforms wrong? Could his failure have been avoided? If Gorbachev’s reforms had succeeded, what would the result have been? Everyone knows my assessment of Gorbachev, but today I’d like to proceed from a different angle and do some more objective analysis, to better understand the Soviet Union. It’s also additional food for thought for China. The Soviet system is not unfamiliar to us. After Gorbachev came to power, the system was already coming close to the “seventy years limit” I’ve spoken of before: it was corrupt and difficult to operate. Its collapse was imminent. Gorbachev followed the historical tide—he put forward the “new thinking” and implemented reform, trying to save the party and the state. Even those people who fume about Gorbachev don’t dare to attack the content of Gorbachev’s reforms. The reason is very simple: how can it be wrong to make the government transparent, destroy totalitarianism, return power to the people, realize democracy, and give people more freedom? No one would be stupid enough to radically criticize the content of Gorbachev’s reforms. Otherwise, even before criticizing Gorbachev, the critic would show himself to be rotten. Reform was necessary. Without reform, the state dies, so reform! But Gorbachev’s reform failed, and his failure caused the ruling party to lose power and led to the collapse of a vast empire. Many people say that the reason for his failure was that the Soviet Union was terminally ill—reform and improvement could not save it. The only options were revolution or waiting for it to die a natural death. The only thing you could do is hope that your own health is good enough so that you could survive a bit longer than the state. There’s some truth to this. For systems like the Soviet Union’s, there was no precedent for successful reform. Gorbachev’s efforts were like walking forward in total darkness, refusing to accept failure until he was forced to. But this argument still does not deter our pursuit for the other reasons Gorbachev’s reforms failed. In hindsight, let’s imagine if Gorbachev’s reform had stuck to “eating the meat” without “biting into the bones.” What if his reform had been small-scale, with lots of noise but little results? Or what if he had tried “crossing the river by feeling the stones” in the economic sphere, gradually relaxing the rigid, planned economy’s control over the public and no longer preventing people’s desire to get rich? In that case, his reform could not have been successful. It also wouldn’t have caused many problems and, what’s more, couldn’t have really failed. Perhaps the Soviet system could have continued for several years or even decades. Gorbachev would have been the envy of his successors, a Soviet version of Deng Xiaoping. But the moment Gorbachev came to power, he went straight to “biting into the bones”: tackling the difficult reforms of the political system and of society. Ordinarily, this is right. The problem was that Gorbachev thought he had a lot of authority. He was very confident about the Soviet system, his “new thinking” theory and his chosen road for reform. Without having gained absolute control of the army, police power, and the authority to reform, he immediately started talking the most difficult reforms. And what was the result? During that short period, when Gorbachev spoke of democracy, Yeltsin was more democratic than him in almost every way. When Gorbachev spoke of adhering to the leadership of the party, party conservatives were more Communist than him in almost every way. He took the lead in loosening control of the media, but the media were not willing to let him off the hook. Almost as soon as the reform began, Gorbachev lost control of it. In less than a few years, he had made enemies of forces inside and outside the system, as well as both the left and the right. To the extreme conservatives, he was seen a as “traitor to socialism,” while at the same time the extreme liberals labeled him a “traitor to democracy and freedom.” Gorbachev’s situation back then was a bit like mine on the internet today: looked down on by both the left and the right. So, was it possible for Gorbachev’s reform to succeed? Not only Gorbachev himself, but also his successors believed this was possible. In fact, at the beginning Gorbachev’s reform, both in its direction and its specific content, actually received support from the enlightened group within the system, from the liberal intellectuals, and from most of the people. If Gorbachev had had more clear goals and a “top-down design” rather than taking a “crossing the river by feeling the stones” mentality into the deep waters of reform; if he had grasped the party, the government, and especially the military and police (KGB) power firmly in his own hands rather than having elder party members dividing his power and challenging his authority; if he had from start to finish placed reform under the leadership of the party rather than listening to the attacks of either conservative or liberal forces—then, from both a tactical and a technical level, the probability of success would have been great. But there is a problem: in accordance with the Soviet system (and we Chinese are very familiar with, aren’t we?), if you want to place reform under the absolute control of Gorbachev, he would need to follow the same practices he is resolved to get rid of. He needed to make a severe extralegal attack on autocracy and corruption within the system—this way he could have avoided the coup that had him imprisoned for three days. He needed to fight a merciless battle against Yeltsin and the rest of the democracy advocates within the party, shutting them up or even putting them under house arrest—this way he could have avoided these figures always taking the high ground during the democratic reform process, having the authorities shoulder responsibility for the “src sin,” and having Gorbachev himself passively suffer scoldings from every direction. Gorbachev needed to triumph over the extreme conservatives and at the same time use more extreme measures to deal with the liberals and the media—this way he could have avoided not having any way to handle them after opening up (instead, in the end, the media almost all rose up to “handle” Gorbachev). But all these steps and measures mean running in the opposite direction of the goal Gorbachev pursued! When Gorbachev tried to make his end and his means consistent, he was quickly eaten up by his own reforms. As the saying goes, “the revolution devours its children.” Even more interesting—this Gorbachev, who was eaten by his reforms, actually cemented his historical legacy by failing. To be clearer: Gorbachev’s failure was his biggest success. Personal success does not necessarily indicate the people’s success; personal failure sometimes actually means historic victory. It’s rare to have failure cement someone’s status as a “great man” in history. Gorbachev is one of these cases. But for a long time, Gorbachev himself did not agree with this type of “greatness.” After stepping down, Gorbachev traveled to the West to give speeches. When people regard him as a hero who overthrew the Soviet Union, he repeatedly said, “If party conservatives and radicals like Yeltsin had not ruined it, my reform would have succeeded, and the Soviet Union wouldn’t have fallen.” Gorbachev’s meaning is clear: if his reform had succeeded, the Soviet Union would have eventually moved toward freedom, democracy and the rule of law, but without Yeltsin’s ten years of chaos (including the economic crisis) and without Putin using an immature democratic system and electorate to create a “dictatorship.” The Soviet Union would not have disintegrated into more than a dozen countries. In the last few years, there have been an immense number of books about the disintegration of the Soviet Union and Gorbachev, but almost nobody has the imagination envision such an outcome: if Gorbachev had succeeded in his reforms, what would the result be? A prosperous, strong, democratic, free Soviet Union as socialist superpower? Or would it only mean Gorbachev’s personal victory—with Gorbachev still serving as the Soviet Union’s chairman and general secretary, becoming, at over 80 years old, one of the world’s longest serving dictators (dwarfing Suharto, Mubarak and Gaddafi)? Gorbachev has left us a textbook full of experiences and lessons. Reform is necessary, there’s no doubt. Few people challenge that the goal and the direction of reform should conform to historical trends, and even the manner, methods and procedures of reform are not an issue. The question is whether or not the leader implementing reform has the authority and power to see the reforms through. After an authoritative leader obtains power, he won’t necessarily reform (for example, leaders such as North Korea’s Kim dynasty, Egypt’s Mubarak and Libya’s Gaddafi). An authoritative leader who is willing to reform may not reform all the way (such as Deng Xiaoping). But a leader who wants to thoroughly reform must hold absolute authority in order to be successful (for example, Taiwan’s Chiang Ching-kuo). Those who deny the direction and content of Gorbachev’s reform must know that going against the tide of history can only delay the inevitable for a short while. If anti-human systems don’t reform, in the end, the leaders and the system will be swept together into the dustbin of history. You have great power, but this only means having the power to bring yourself historical shame. Today, China in many respects has already surpassed the reforms Gorbachev pushed forward in the Soviet Union. At the same time, those who hope for a Chinese Gorbachev should realize no leader in the world is willing to be eaten by his own reforms. In China, aren’t there even fewer leaders in the reform school who are willing to be destroyed by the reforms they began and promoted? The historical choices are not many. How can we choose the path of Gorbachev’s reform, but without repeating his mistakes? How can we be a successful Gorbachev—neither the Gorbachev whose reforms failed, nor the Gorbachev who is thought successful because his reforms failed, but a Gorbachev whose reforms succeed? Obviously, this requires not only political ideals, but also political authority, political wisdom, and political skill. At a time when the Russians have gradually forgotten Gorbachev, and Western enthusiasm for him has died, China’s “Gorbachev complex” is still going strong. History cannot be predicted. The Soviet Union’s reform has already ended, but China’s reform is not only not finished, but new reforms are just getting started. China, with a system similar to the Soviet Union’s, is still walking alone on the path towards the future. China needs a reforming Gorbachev, but this Gorbachev definitely won’t hope for his own reforms to fail. I’m talking about the Soviet Union and Gorbachev, and taking the 83-year old Gorbachev as my target—this must really disappoint those friends who wanted to hear me throw out incisive opinions on China’s political situation. Please allow me to make a joke: if I were Gorbachev, what would I do? I guess I would have no choice. I would follow the historical tides, and make a top-down plan to lead the Soviet Union towards freedom, democracy, the rule of law, and prosperity. I would seize control of the military police and the national security apparatus, secure the power to initiate reforms, defeat the extreme forces on both the left and the right, and then implement reform measures step by step… Unfortunately, I’m not Gorbachev, and even though I’m forcing myself to imagine Gorbachevs, I actually don’t have much confidence in the system he represents. So I tend to agree that Gorbachev’s great success lies in his failure. I hope that in the future Gorbachev can succeed, and transform his success into the success of the people, the country, and the nation. This piece srcly appeared in Chinese on Yang Hengjun’s blog. The src post can be found here. Yang Hengjun is a Chinese independent scholar, novelist, and blogger. He once worked in the Chinese Foreign Ministry and as a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington, DC. Yang received his Ph.D. from the University of Technology, Sydney in Australia. His Chinese language blog is featured on major Chinese current affairs and international relations portals and his pieces receive millions of hits each day. Yang’s blog can be accessed at www.yanghengjun.com 原文: 做一名成功的戈爾巴喬夫? 文 | 楊恒均 今天主持人邀請我談談中國政局,但一談這個,我就要發牢騷、就要批評,可我早就立下了規矩,不在海外批評中國,要批評中國,我會回國再批。所以,我今天只能講講戈爾巴喬夫,一位外國退休的領導人,八十多歲了,講起來很安全。 中國朝野的“戈爾巴喬夫情結”非常嚴重,有人希望中國盡快出一名戈爾巴喬夫,有人在竭力避免中國的戈爾巴喬夫出現。想中國出戈爾巴喬夫,是因為他銳意改革,幾乎是以一人之力結束了冷戰,終結了強大但相當邪惡的蘇聯帝國,給俄羅斯等國家帶來了民主。有人討厭戈爾巴喬夫,是因為這位老兄的改革失敗了,不但導致執政的共產黨下崗,還讓超級大國一夜之間分崩離析,連接下來20多年的民主轉型也不那么平穩。 戈爾巴喬夫的改革錯了嗎?他的失敗是可以避免的嗎?如果戈爾巴喬夫的改革成功了,又會有什么樣的結果?——大家都知道我對戈爾巴喬夫的評價,但今天我想從另外一個角度和層面做一些更加客觀的分析,讓各位了解蘇聯——也對中國多一份思考。 蘇聯體制大家都不陌生,到了戈爾巴喬夫上臺后,已接近我說的“七十年大限”:腐化墮落,幾乎難以運轉,倒臺是分分鐘的事,戈爾巴喬夫順應歷史潮流,提出了“新思維”,進行改革,試圖挽救黨和國家。即便那些對戈氏咬牙切齒的人,也沒有敢對戈氏改革的內容進行攻擊的,原因很簡單,難道透明政府、瓦解極權、還權于民、實現民主、給人民更多自由會錯嗎?沒有人會傻到對戈氏的改革內容提出過激的批判,否則他還沒有批倒戈氏,自己就先臭了。 改革是必須的,不改亡國,改了呢——戈氏的改革失敗了,他的失敗導致執政黨下臺,引發一個龐大帝國的瓦解。很多人說失敗的原因是因為蘇聯得的是絕癥,改革改良都挽救不了它,只能革命,或者等它自然死亡,你唯一能做的就是希望自己身體夠好,能夠活得比它更長一些。這話不是沒有道理,像蘇聯這樣的體制,確實沒有改革成功的先例,幾乎都是一頭走到黑,不見棺材不掉淚。但這還是不影響我們追尋戈爾巴喬夫改革失敗的其它一些原因。 回頭看看,戈氏的改革如果是只吃肉不啃硬骨頭,小打小鬧,風聲大雨點小,或者在經濟領域摸石頭過河,逐步放寬僵化計劃經濟對民眾的控制,不阻止民眾致富的愿望,他的改革即便不能成功,也不會出多大的問題,就更不會失敗了,蘇聯體制很可能繼續延續幾年甚至幾十年。戈氏也就成了他后來比較羨慕的蘇聯版的鄧小平。但戈爾巴喬夫一上來就去啃硬骨頭,搞政治體制與社會改革。 這個按說也沒錯,問題是他以為自己很有權威,對蘇聯的制度、他的“新思維”理論以及他選定的改革之路都很自信,大有“四個自信”的勢頭。在沒有絕對掌握軍、警大權以及改革的領導權之下,就開始了啃硬骨頭的改革,結果怎么樣呢? 有那么一段時間,戈爾巴喬夫一說民主,葉利欽幾乎樣樣都比他更民主;他一說堅持黨的領導,黨內保守派幾乎都比他更共產黨;他率先放開對媒體的控制,媒體卻都不愿意放過他。改革一開始,他幾乎就失去了對改革的控制,幾年不到,他把體制內外和左右兩派都得罪了,被極端保守派視為“社會主義的叛徒”,同時又被極端自由主義分子貼上了“民主、自由的叛徒”的標簽——戈氏當年的境況,很有點像老楊頭當今在網絡上的處境:左右不是人啊。 那么,戈氏的改革有可能成功嗎?不但戈氏自己,他的后繼者也都認為有這個可能。事實上,戈爾巴喬夫的改革無論從方向還是具體的內容上,一開始是確實得到了體制內開明派、廣大知識分子以及大部分求變民眾的支持的。如果戈爾巴喬夫能有更明確的目標和“頂層設計”,而不是在改革進入深水區后還抱著“摸石頭過河”的心態,如果他能把黨、政尤其是軍、警(克格勃)的大權都牢牢掌握在自己手中,而不是被黨內的老人指手畫腳分掉了權力、損害了權威,如果他始終把“改革置于黨的領導之下”(戈氏語)而不是聽任體制內保守派以及極端民主派對自己左右夾擊,他的改革從戰術和技術層面來說,成功的可能性還是很大的。 只不過這就出現了一個問題:按照蘇聯的體制(我們都很熟悉,不是嗎),如果要做到把改革始終置于戈爾巴喬夫的絕對領導之下,他必須得做的正是他立志要改掉的:對體制內的專權與腐敗不通過法律手段進行嚴厲的打擊(從而避免那些將軍和克格勃發動政變,把他囚禁在別墅三天之久),對黨內民主派葉利欽等人進行無情的斗爭,讓他們閉嘴甚至軟禁起來(而不讓他們總是在民主改革的進程中占據道德制高點,讓當局背負“原罪”,讓戈氏自己處處被動挨罵),把極左派弄得灰頭灰臉,同時對自由派和媒體采取更加嚴厲的措施(而不是放開后無法收拾,最終媒體幾乎都起來對付戈氏本人)…… 可是,所有這些手段和措施卻又同他追求的改革目標背道而馳!而當戈氏試圖讓追求的目標和手段一致時,他很快就被自己發起的改革吃掉了,正如“革命吃掉了自己的兒子”一樣。 更有意思的是,被改革吃掉了的戈爾巴喬夫,卻以他的失敗奠定了自己的歷史地位。說白一點就是:戈爾巴喬夫的失敗正是他最大的成功。 個人的成功不一定預示民眾的成功,個人的失敗有時反而是歷史的勝利。歷史上很少有以失敗奠定自己歷史地位的“偉人”,戈爾巴喬夫就是其中之一。但相當長一段時間里,戈氏自己并不認同這種“偉大”。下臺后的戈氏到西方各地演講,當人家把他當成推翻蘇聯的英雄時,他自己卻像祥林嫂一樣反復叨念諸如“如果不是黨內保守派和激進的葉利欽等人的破壞,我的改革會成功,蘇聯也不會倒”。戈氏的意思很清楚:如果他的改革成功了,蘇聯最終也會走向自由、民主與法治,反而少了葉利欽十年的混亂(包括物資匱乏)和普京十幾年利用不成熟的民主體制與選民而搞的“獨裁”,蘇聯也不會解體成十幾個國家…… 這些年論述蘇聯解體和戈爾巴喬夫的書汗牛充棟,可幾乎沒人有想像力設想這樣一種結局:如果戈氏的改革成功了會怎樣?一個繁榮、富強、民主、自由的蘇聯社會主義超級大國?或者那只不過是戈爾巴喬夫個人的勝利——能夠讓戈氏至今還盤踞在蘇聯國家主席與總書記的寶座上,成為80高齡、執政最久的獨裁者之一?讓蘇哈托、穆巴拉克和卡扎菲都相形見拙? 戈爾巴喬夫給我們留下了一本充滿經驗和教訓的教科書:必須改革,這沒有疑問;改革的目標和方向也應該是符合歷史大趨勢,這個也沒有多少人敢質疑和挑戰,甚至改革的方式方法和步驟也不是問題,問題在于實行改革的領導人是否有權威與權力把改革進行到底。有權威的領導人掌握大權后并不一定會改革,例如金家王朝、穆巴拉克和卡扎菲之流的;有權威的領導人愿意改革的,也不一定一改到底,例如鄧小平;但愿意徹底改革的領導人必須掌握絕對的權威,才能獲得成功,例如蔣經國。 那些否定戈爾巴喬夫改革內容和方向的人必須認識到,倒行逆施只能讓你茍延殘喘一段時間,反人類的體制不改革,最終領導人和體制一起都會被掃進歷史的垃圾堆。你擁有再大的權力,只不過是有權把自己的貼在歷史的恥辱柱上而已。戈爾巴喬夫當年在蘇聯推行的改革,中國目前在很多方面都有過之而無不及。 同時,那些希望中國出現戈爾巴喬夫的人也應意識到,世界上是沒有哪一個領導人愿意被自己發起的改革吃掉。在中國,被自己發起和推動的改革吃掉的改革派領導人還少嗎? 歷史留下的選擇并不多,如何選擇戈爾巴喬夫的改革道路,卻又不重蹈他的覆轍,如何當一名成功的戈爾巴喬夫——不是那個改革失敗的戈爾巴喬夫,也不是那個因改革失敗而被認為成功了的戈爾巴喬夫,而是當一名成功改革的戈爾巴喬夫!很顯然,這不但需要政治理想,也需要政治權威、政治智慧甚至政治手腕。 就在俄國人逐漸淡忘戈爾巴喬夫,西方人的熱情不再之時,中國的“戈爾巴喬夫情結”卻方興未艾。歷史不能假設,蘇聯的改革早已結束,但中國的改革非但沒有結束,反而新的改革才剛剛起步,類似蘇聯體制的中國依然在通往未來的道路上踽踽獨行。中國需要改革的戈爾巴喬夫,但改革的戈爾巴喬夫們肯定不希望自己的改革會失敗。 各位,我講了一通蘇聯與戈爾巴喬夫,讓八十多歲、躺著的戈氏也中槍了,也讓想聽我對中國政局發飆犀利看法的朋友失望了。最后請允許我開個玩笑:假如我是戈爾巴喬夫,我會怎么做呢?我想我別無選擇,我會順應歷史潮流,搞一個使蘇聯走向自由、民主、法治與富強的頂層設計,然后我會緊緊抓住對軍警以及國家安全的控制,掌握改革的主動權,把左右等極端派都打下去,然后一步一步去實施自己的改革措施—— 可惜我不是戈爾巴喬夫,而且即便我強迫自己對戈爾巴喬夫們抱有幻想,我也對他代表的那個體制實在沒有多少信心,所以,我還是傾向認同戈爾巴喬夫的最大成功就在于他的失敗。希望未來的戈爾巴喬夫們能夠成功,并把他們自己的成功變成人民、國家和民族的成功! 謝謝各位! 楊恒均 2014.2.21Being a Successful Gorbachev?

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

楊恒均 2015-08-23 08:53:39

評論集

暫無評論。

稱謂:

内容:

返回列表